December 16, 2016 Little Known Facts

Presented by Nelson Thibodeaux, Editor LNO from Columbia Journal Review

The real history of fake news

Header Photo (Composing room of the New York Herald (no date recorded) (Photo: Library of Congress)

“It is a melancholy truth, that a suppression of the press could not more compleatly [sic] deprive the nation of its benefits, than is done by its abandoned prostitution to falsehood,” the sitting president wrote. “Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle.”

That vehicle grew into a commercial powerhouse in the 19th century and a self-reverential political institution, “the media,” by the mid-20th. But the pollution has been described in increasingly dire terms in recent months. PolitiFact named fake news its 2016 “Lie of the Year,” while chagrined Democrats have warned about its threat to an honest public debate. The pope compared consumption of fake news to eating feces. And many of the wise men and women of journalism have chimed in almost uniformly: Come to us for the real stuff.

“Whatever its other cultural and social merits, our digital ecosystem seems to have evolved into a near-perfect environment for fake news to thrive,” New York Times CEO Mark Thompson said in a speech to the Detroit Economic Club on Monday.

The broader issue driving the paranoia is the tardy realization among mainstream media that they no longer hold the sole power to shape and drive the news agenda.

A little bit of brake-tapping may be in order: It’s worth remembering, in the middle of the great fake news panic of 2016, America’s very long tradition of news-related hoaxes. A thumbnail history shows marked similarities to today’s fakery in editorial motive or public gullibility, not to mention the blurred lines between deliberate and accidental flimflam. It also suggests that the recent fixation on fake news has more to do with macro-level trends than any new brand of faux content.

Macedonian teenagers who earn extra scratch by concocting conspiracies are indeed new entrants to the American information diet. Social networks allow smut to hurtle through the public imagination—and into pizza parlors—at breakneck speed.

But put aside the immediate election-related PTSD and the rampant self-loathing by journalists, which has led to cravings for a third-party, perhaps Russian-speaking, fall guy. The broader issue driving the paranoia is the tardy realization among mainstream media that they no longer hold the sole power to shape and drive the news agenda. Broadsides against fake news amount to a rearguard action from an industry fending off competitors who don’t play by the same rules, or maybe don’t even know they exist.

“The existence of an independent, powerful, widely respected news media establishment is an historical anomaly,” Georgetown Professor Jonathan Ladd wrote in his 2011 book, Why Americans Hate the Media and How it Matters. “Prior to the twentieth century, such an institution had never existed in American history.” Fake news is but one symptom of that shift back to historical norms, and recent hyperventilating mimics reactions from eras past.

Take Jefferson’s generation. Our country’s earliest political combat played out in the pages of competing partisan publications often subsidized by government printing contracts and typically unbothered by reporting as we know it. Innuendo and character assassination were standard, and it was difficult to discern content solely meant to deceive from political bomb-throwing that served deception as a side dish. Then, like now, the greybeards grumbled about how the media actually inhibited the fact-based debate it was supposed to lead.

“I will add,” Jefferson continued in 1807, “that the man who never looks into a newspaper is better informed than he who reads them; inasmuch as he who knows nothing is nearer to truth than he whose mind is filled with falsehoods & errors.”

Decades later, when Alexis de Tocqueville penned his seminal political analysis, Democracy in America, he also assailed the day’s content producers as men “with a scanty education and a vulgar turn of mind” who played on readers’ passions. “What [citizens] seek in a newspaper is a knowledge of facts,” de Tocqueville wrote, “and it is only by altering or distorting those facts that a journalist can contribute to the support of his own views.” His concerns weren’t for passive failures of journalism, but active manipulation of the truth for political ends.

While circulation in those days was relatively low—high publishing costs, low literacy rates—proliferation of multiple titles in each major city provided a menu of worldviews that’s similar to today. The infant republic nevertheless managed to survive the fake news scourge of early 19th-century newspapermen. “The large number of news outlets, the heterogeneity of the coverage, the low public esteem toward the press, and the obvious partisan leanings of publishers limited the power of the press to be influential,” political scientist Darrell M. West wrote in his 2001 book, The Rise and Fall of the Media Establishment.

With the growth of the penny press in the 1830s, some newspapers adopted advertising-centric business models that required much larger audiences than highbrow partisan opinions would attract. So the motivation to mislead shifted slightly more toward commercially minded sensationalism, spurring some of the most memorable media fakes in American history.

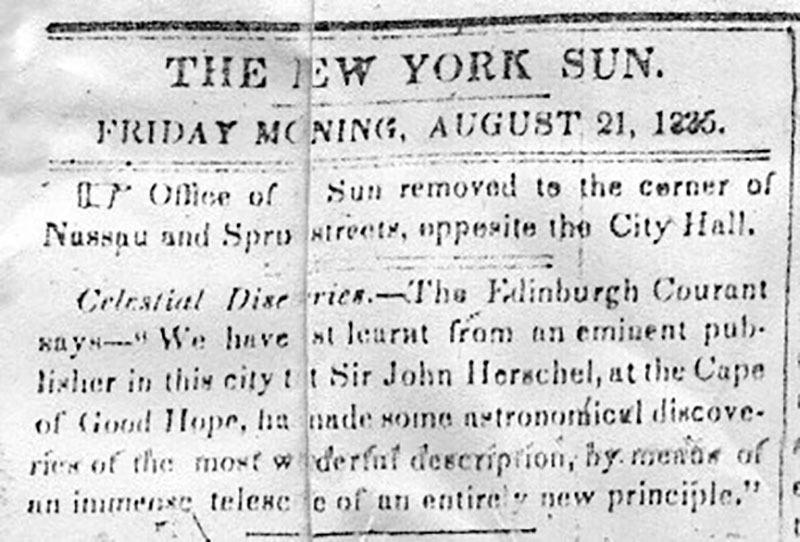

In 1835, The New York Sun ran a six-part series, “Great Astronomical Discoveries Lately Made,” which detailed the supposed discovery of life on the Moon. The hoax landed in part because the Sun’s circulation was huge by standards of the day, and the too-good-to-be-true story supposedly enticed many new readers to fork over their pennies as well.

Top: The front page of The New York Sun from August 25, 1835, the day the paper launched its six-part hoax. Bottom: A teaser for the series published four days earlier. (Courtesy: The Museum of Hoaxes)

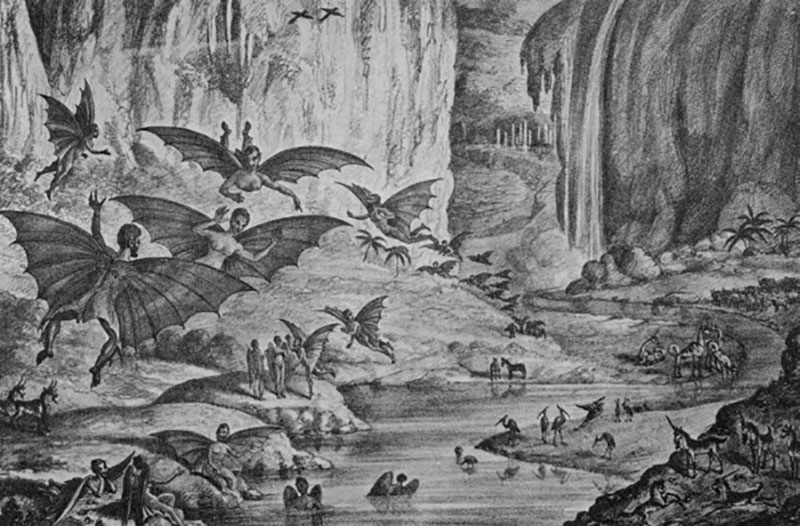

Edgar Allan Poe, who weeks before had published his own moon hoax in the Southern Literary Messenger, quickly criticized the Sun story’s unbelievability—and the public’s gullibility. “Not one person in 10 discredited it,” Poe recounted years later. He went on to chastise the Sun’s fake news story for what he saw as low production value:

Immediately upon completion of the ‘Moon story’…I wrote an examination of its claims to credit, showing distinctly its fictitious character, but was astonished at finding that I could obtain few listeners, so really eager were all to be deceived, so magical were the charms of a style that served as a vehicle of an exceedingly clumsy invention….Indeed, however rich the imagination displayed in this fiction, it wanted much of the force that might have been given to it by a more scrupulous attention to analogy and fact.

Many other newspapers were skeptical of the Sun’s moon story. But public backlash was muted in part because of the lack of widely accepted standards for the content appearing in readers’ news feeds, not unlike today. Objective journalism had yet to settle in, and there were no clear dividing lines between reporting, opinions, and nonsense. The public’s credulity—potentially embellished by Poe and other contemporaneous accounts—became part of the legend, particularly given elites’ apprehension of Jacksonian populism.

A print depicting one of the scenes described in the moon hoax, date unknown (Courtesy: The Museum of Hoaxes)

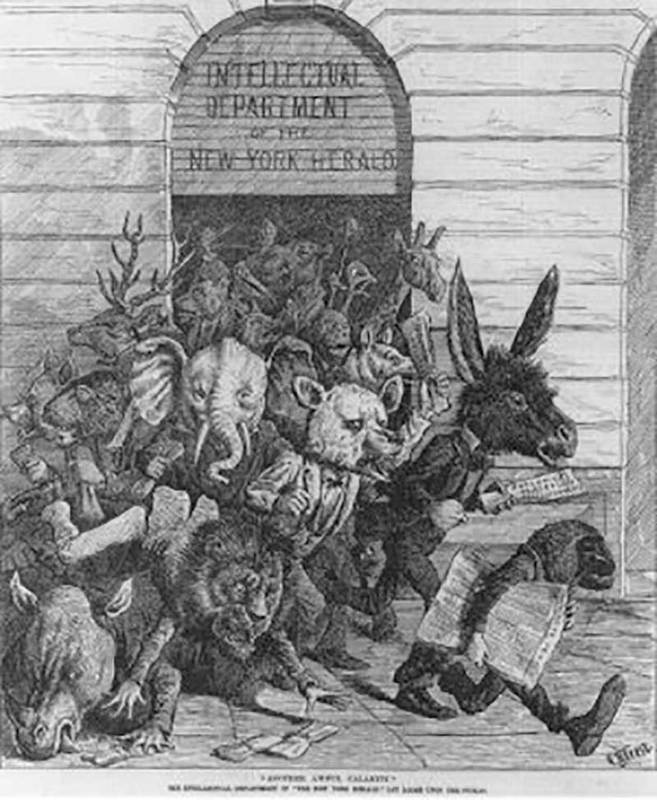

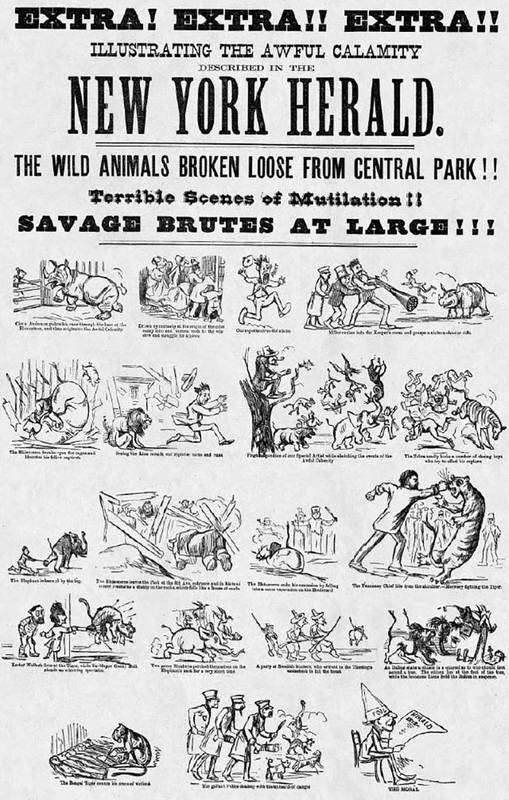

These historic purveyors of fake news were by no means obscure publications from the 19th-century equivalent of the digital gutter. In 1874, the widely read New York Herald published a more than 10,000-word account of how animals had broken out of the Central Park Zoo, rampaged through Manhattan, and killed dozens. The Herald reported that many of the escaped animals were still at large as of press time, and the city’s mayor had installed a strict curfew until they could be corralled. A disclaimer, tucked away at the bottom of the story, admitted that “the entire story given above is a pure fabrication. Not one word of it is true.”

“Another Awful Calamity. The Intellectual Department of The New York Herald Let Loose Upon the Public.” 1874 cartoon by A. B. Frost satirizing the Herald’s zoo hoax. (Wikimedia)

Many readers must have missed it. The hoax quickly spread through real-life social networks, as historian Hampton Sides described in his 2014 book, In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette:

Alarmed citizens made for the city’s piers in hopes of escaping by small boat or ferry. Many thousands of people, heeding the mayor’s ‘proclamation,’ stayed inside all day, awaiting word that the crisis had passed. Still others loaded their rifles and marched into the park to hunt for rogue animals.

An 1893 Harper’s Weekly illustration that accompanied an article about the zoo hoax. (Courtesy: The Museum of Hoaxes)

Even as the late-19th and early-20th centuries saw the early stages of the shift toward a more professionalized media, corruption of the information that reached readers remained common. In his 1897 book critiquing American news coverage of the Cuban War of Independence, Facts and Fakes about Cuba, George Bronson Rea outlined the stages of embellishment between minor news events outside of Havana to seemingly fictionalized front-page stories in New York. Cuban sources wanted to turn public opinion against Spain, while American correspondents were eager to sell newspapers.

“But the truth is a hard thing to suppress,” Rea wrote, “and will sooner or later come to light to act as a boomerang on the perpetrators of such outrageous ‘fakes,’ whose only aim is to draw this country into a war with Spain to attain their own selfish ends.”

There are fewer glaring examples of fake news stretching toward the mid-20th century, as journalistic norms—as we conceive of them today—began to emerge. Commercial monopolies, coupled with lack of political partisanship, gave news organizations daylight to professionalize and police themselves. But that’s not to say this golden era was free from myths.

They’re neat and tidy, easy to remember, fun to tell, and media centric,” Campbell says in an interview. “They serve to elevate media actors. There is an aspirational component to these myths that help keep them alive.”

Indeed, many uncorrected stories concern the news media itself, which could provide clues as to why today’s notion of fake news seems to have so much cultural currency. As American University Professor W. Joseph Campbell debunks in his book, Getting It Wrong: Ten of the Greatest Misreported Stories in American Journalism, a remark by Walter Cronkite wasn’t actually the first domino to fall en route to ending the Vietnam War. The Washington Post didn’t really bring down Nixon. (Media coverage and public opinion toward the war had already gone south; Nixon was felled by subpoena-wielding authorities and a wide array of other constitutional processes.)

The opposite force could be at play in today’s fake news debate. Public trust of the media has been in decline for decades, though the situation now feels particularly cataclysmic with the atomization of media consumption, partisan criticism from all corners, and the ascension of Donald Trump to the White House. Just as Watergate gave the media a bright story to tell about itself, fake news provides a catchall symbol—and a scapegoat—for journalists grappling with their diminished institutional power.

It’s telling that the most compelling reporting on fake news has focused on distribution networks—what’s new—even if those stories have yet to prove they’ve exacerbated the problem en masse. In the meantime, let’s retire the dreaded moniker in favor of more precise choices: misinformation, deception, lies. Just as the media has employed “fake news” to discredit competitors for public attention, political celebrities and partisan publications have used it to discredit the press wholesale. As hard as it is to admit, that’s an increasingly unfair fight.